|

|

Alec Finlayson Pty Ltd v Armidale City Council

This case study considers litigation for negligence against a NSW local government, Armidale City Council, in which the council was successfully sued by a builder who purchased contaminated land that the council had approved for development as a residential estate.

It is a rare example of a government authority successfully being sued for negligent decisions.

It is good example for government staff, town planners and other environmental professionals to understand their professional duties to avoid negligence.

History of the contaminated site

In 1967 the council approved the construction of a timber treatment plant on the site. The plant included a large pressure cylinder (22 meters long) to impregnate telephone poles and other timber items with creosote, a wood preservative, which contains compounds with a number of toxic effects, including carcinogenicity.

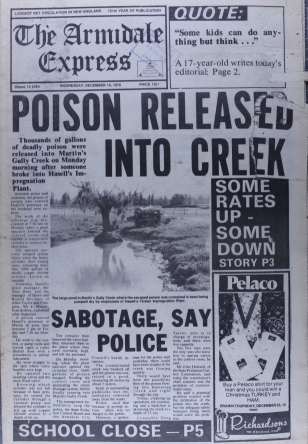

The timber treatment plant commenced operation in 1968 (see a local news report here) and in the following decade multiple pollution incidents at the plant were recorded by council officers.

Steps agreed between council and the plant operator to rectify the problems proved in adequate. There were ongoing complaints from neighbours and creosote was found in a creek some 200-300 metres away and in the road adjacent to the plant.

In 1970 council approved plans for the installation of two new tanks to contain tanalith, a toxic, complex salt containing arsenic in the form of copper chrome arsenate.

In 1976 about 3,000 gallons (11,000 litres) of copper chrome arsenate escaped from the pressure cylinder and heavily contamined the site and a section of the nearby creek. A news story of the incident is available here.

The timber treatment plant operated until 1979 or 1980 when the plant was relocated.

Historic photographs of the timber treatment plant are available here.

Evidence of a former employee

A former employee at the timber treatment plant who gave evidence at the trial described the complete lack of any proper disposal system for waste on the site.

One of the jobs he and other workers did was to get rid of waste from the pressure cylinder.

He gave evidence that it was tipped into 44-gallon drums then dumped elsewhere on the site.

He said disposal of the waste around the site "was rampant" and "that is the only way they got rid of the liquid".

Residential development approved by council

In 1982 a development company bought the land. In 1984 it applied to council for a residential subdivision in two stages.

Council approved the first stage, but Burchet J found in evidence at the later trial:

"Arsenic and PAH are present, in the main, in the upper layer of gravelly ground, which could have been removed and replaced before the land was subdivided. Once houses were erected, the problem was magnified. Arsenic and PAH are carcinogenic as well as toxic, and where both are involved there may be a synergistic effect, presenting a particular hazard in areas in which young children may play ... and vegetables grown in backyard gardens may take up substances from the soil.

... there is also evidence that turning over of the soil has revealed visible creosote, and the offensive smell of creosote has invaded homes on the land."

In 1985 the second stage of the residential subdivision was sold to a local builder, Alec Finlayson Pty Ltd, which applied to council to subdivide the land into 27 lots for housing.

Council approved the application and the builder proceeded with the development.

In subsequent years the builder made further applications for development of the land, bought surrounding land, and constructed and sold houses on the land.

It was only in 1990, after much of the land had been built on, that the serious contamination was revealed.

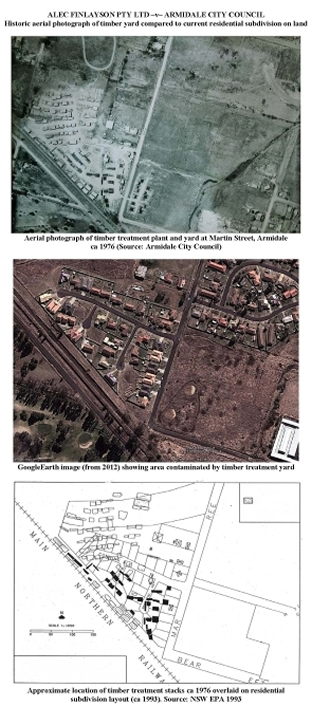

A historic aerial photograph showing the timber yard (ca 1976) compared to the residential subdivision is available here. Photographs of the residential subdivision in 1995 are available here.

Litigation

The builder sued the council and the company that had sold it the contaminated land. The claim against the latter did not proceed as the company was in liquidation (Gow and Taylor 1996).

The proceedings were brought in the Federal Court as they initially involved an application under the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) and in negligence at common law, but the former claim was dropped at the hearing (Gow and Taylor 1996).

The trial judge, Burchett J, found that, given the history of the site that was known to the council, it had been negligent in approving a residential development of the land without requiring proof that the land was in fact suitable for subdivision for residential use.

Burchett J found (at [64]):

"I am satisfied that, in fact, the risk of persisting chemical contamination was not taken into consideration at any stage of the determination of any of the development applications. If it had been, some action would certainly have followed, given the known history of the site."

Burchett J found that the council had breached its duty of care in approving the development of the land and awarded $1,479,576 in damages and interest to Finlayson.

The decision was upheld on appeal.

Key documents in this case were:

Pleadings

- Statement of claim

- Second Further Amended Statement of Claim

- Third Further Amended Statement of Claim

- Amended Defence of First Respondent to Further Amended Statement of Claim

- Defence of Second Respondent

- Cross claim (by second respondent)

- Second Cross Claim (by first respondent / council)

- Defence of Cross-Respondent to Cross Claim

Evidence

- Affidavit of Laurence Knight (valuer) [copied in black and white]

- Catalogue of photographs of the contaminated land and surrounds (in colour) from the affidavit of Laurence Knight (valuer)

- Historic aerial photograph of timber yard compared with current residential subdivision on land [not tendered in evidence at trial].

- Historic photographs of the timber treatment plant.

Decisions

- Trial decision finding council was negligent: Alec Finlayson Pty Ltd v Armidale City Council & Anor [1994] FCA 1198; 51 FCR 378; 123 ALR 155

- Decision on the principles to be applied in assessing damages: Alec Finlayson Pty Ltd v Armidate City Council [1997] FCA 1517

- Trial decision assessing damages: Alec Finlayson Pty Ltd v Armidale City Council [1998] FCA 170

- Full Court decision dismissing council's appeal: Armidale City Council v Alec Finlayson Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 330; 104 LGERA 9.

References

Gow S and Taylor L, "Contaminated land – legal liabilities for local government and a possible response" (1996) 1 Local Government Law Journal 154-163.

Front page story of The Armidale Express, 15 December 1976, concerning pollution from the site. To read the article, click here for a high quality & legible version of this image.

Historic aerial photograph of timber yard compared with current residential subdivision on land. To see a higher quality and legible version of these images, click here.

Thanks to Stephen Gow at Armidale City Council for providing the historic aerial photographs and other historic images used in this case study.

Thanks to the Federal Court of Australia Sydney Registry for supplying the pleadings and affidavits used in this case study.

Thanks to Katherine Pearson from the Environmental Defenders Office NSW for inspecting the Federal Court file and obtaining the pleadings and photographs in the valuer's report.